After years of incubation within the confines of the enterprise IP network, IP-based fax has recently entered a period of rapid and increasingly broad adoption. Business users are now pushing beyond the enterprise network, which uses on-premises gateways—let’s call that IP Fax Phase I–and are now directly connecting with the IP service provider via SIP trunking or direct SIP peering—IP Fax Phase II–obviating the need for the enterprise gateway. However, not all local-access providers are ready with effective IP-fax support, and the backbone IP providers have only recently begun the move to provide for the transport of quality IP-based fax. International IP fax, peered between national carriers, has yet to get underway.

As with any introduction of a new technology, this transition period of IP-fax adoption is not without challenges. It requires effective internetworking between the enterprise and the access provider, and between the access provider and long-haul IP networks, often resulting in several tandem connections. And ironing out the kinks isn’t always simple, as it requires an unusual degree of inter-vendor cooperation. Moreover, if a fax session transits the open Internet, the use of T.38 fax relay is usually required for reliable fax transmission, and T.38 support is still uneven. So, much of the challenge for users and service providers is to find partners and vendors that support T.38 in their equipment and networks and are willing and able to solve session-setup problems. Then, we must overcome firewall, network address translation, registration, authentication, routing, and T.38 handoff challenges

But prior to reviewing this transition period one step at a time, let’s settle on a definition of fax, since that’s what this paper is about and there seems to be some confusion as to what is a “fax/facsimile”? We can actually turn to the courts for an answer. It turns out there is some amount of intellectual-property legal jousting going on out there, and one case actually resulted in a definition of “facsimile” or faxing. One ruling from the Federal District Court of Central California (paraphrasing) defines the word “fax,” or “facsimile,” as image data transmitted between two endpoints (fax terminals) that use the T.30 protocol to govern the transaction. This means, for example, that sending or receiving an e-mail with an attached image file is not “faxing” or sending a fax. T.30 is the international standard that specifies the procedures for computer-to-computer (yes, all G3 fax terminals are computers) image exchange. If T.30 isn’t being executed on each end of the exchange, it isn’t a fax, and this paper is about fax.

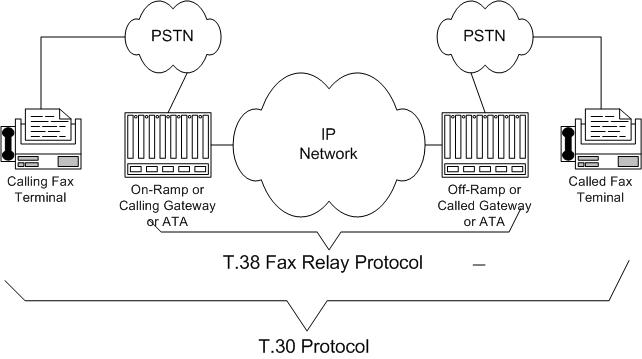

But T.30 and its related recommendations, such as T.4, T.6, and the fax-modems, were developed prior to the Internet’s use as a telephony transport, and the timing restrictions of T.30 usually can’t be maintained when using an error-correcting protocol, such as TCP, so PCM streams are transported using UDP, a best-effort protocol, combined with an additional protocol, T.38. T.38’s job is to make an interposing IP network transparent to two communicating T.30 endpoints, as shown in the figure below.

The network diagram shows two fax terminals communicating using the T.30 protocol and two IP-PSTN gateways communicating using T.38. If the gateways and their T.38 do their job, the two fax machines are “unaware” that there is an IP network involved. T.38 makes an interposing IP network transparent to the two T.30 terminals.

But not all gateways, especially those more than five years old, support T.38. And even if the gateways support T.38, the IP-network operator may not offer a T.38 service. Without T.38, these less-capable gateways and networks will try to complete the fax transaction with what is known as “G.711 pass through.” G.711 is simply the encoding scheme used to represent analog signals, such as voice and modem, on digital telephone networks. There are usually a few differences between how voice and modem data are handled, but basically, these gateways try to transport the fax session’s modem signals as though they were voice. However, modems are much less tolerant of packet loss than our ears, so G.711 pass-through can result in image errors and dropped calls when packet loss occurs, while a voice call might sound just fine. This does not mean that G.711 pass through should not be used for fax. There are some applications, such as a high-speed enterprise LAN or metro-network, where it works just fine. (But beware of long pages sent using super-fine resolution even in these controlled environments.)

Note that performance and interoperability of T.38 implementations vary widely. Performance metrics include the ability to handle missing, late, and out-of-order packets of a T.38 implementation, and can be very poor, even when the interoperability may be excellent. Interoperability results from effective implementation of the T.38 recommendation; performance results from years of fax-technology experience and effective design of the developer. Less-capable T.38 implementations can only handle packet delays of a few 100-milliseconds or so, while the best implementations handle nearly five seconds of delay, supporting the delays inherent in geosynchronous-satellite links.

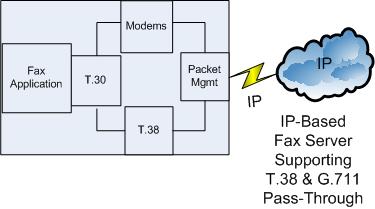

Finally, let’s settle on one more term: “terminating T.38”. Take a look at the figure on the previous page. Now, remove the PSTN network on one side and you remove the need for analog modems in the gateway function. Then, combine the function of the two remaining network elements on that side, the fax terminal and the gateway, and you have “terminating T.38”, the integration of T.30 and T.38 in one system, as shown in the figure to the right. Terminating T.38, invented and shipped by Commetrex in 2001, is the function that allows fax servers to send and receive faxes within an IP network. T.38 is used for fax transport in lieu of the analog modems used for TDM networks. Think of the T.38 protocol engine in an IP network as being functionally equivalent to the analog modems in a TDM network (or G.711 pass through in an IP network without T.38 support). Of course, all of these entities use T.30 as the end-to-end protocol.)

Finally, let’s settle on one more term: “terminating T.38”. Take a look at the figure on the previous page. Now, remove the PSTN network on one side and you remove the need for analog modems in the gateway function. Then, combine the function of the two remaining network elements on that side, the fax terminal and the gateway, and you have “terminating T.38”, the integration of T.30 and T.38 in one system, as shown in the figure to the right. Terminating T.38, invented and shipped by Commetrex in 2001, is the function that allows fax servers to send and receive faxes within an IP network. T.38 is used for fax transport in lieu of the analog modems used for TDM networks. Think of the T.38 protocol engine in an IP network as being functionally equivalent to the analog modems in a TDM network (or G.711 pass through in an IP network without T.38 support). Of course, all of these entities use T.30 as the end-to-end protocol.)

Currently, terminating T.38 is sweeping the enterprise-fax industry, as businesses have dramatically reduced investments in TDM-based systems (or at least in TDM systems that can’t be easily upgraded to IP-based systems). Enterprise-fax vendors are scrambling to make sure they have a solid, cost-effective terminating-T.38 solution.

So, let’s look at where FoIP is today, how we got here, and where it’s headed.